EU-ETS will need tweaking after climate treaty

“The polluter pays” is the main principle in emissions trading. However, despite being the central pillar of EU climate protection, emissions trading has become a betting shop for policy decisions. A new study shows that the EU emissions trading scheme (EU-ETS) is controlled by announcements rather than by supply and demand. MCC researchers suggest the introduction of a minimum price.

The price of EU emission allowances has plummeted, in turn compromising the clout of this climate policy instrument. Only ten percent of this drop in value is due to the recession and renewables. A new study shows that most carbon price drops, many of which were quite drastic, were caused by politics. “Many political announcements and decisions were forcefully acknowledged by the market, and almost always negatively—even in the case of positive news,” said Dr. Nicolas Koch, lead author of the study of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) in Berlin.

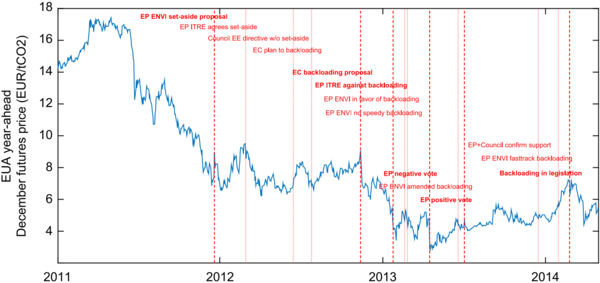

Koch, examining 29 political events taking place between 2008 and 2014, observed that many had an effect on the carbon price. The sensitive interplay of emissions trading and politics became particularly evident from November 2012 on (see figure). Back then, a tonne of CO2 cost nine euros. That was the last peak before the price fell to below three euros. The latter drop was triggered in large part by the European Union with its proposal to put a five-year freeze on emission permits, also called backloading. “The intention, of course, was to boost prices, but the opposite happened,” said Koch.

Indeed, backloading was accompanied with a lengthy political tug of war. “To date, this is precisely where the problem lies,” explains the MCC researcher. “The market is decreasingly expecting anything to change or that the EU will implement its climate goals by means of rising carbon prices.” A low point was reached when the European Parliament rejected the backloading proposal several months later. On that day, the price plunged by almost 43 percent—a fiasco that even a subsequent vote in favor of backloading could do little to revert.

“In the absence of a clear policy, traders are left to guess what might happen next,” says MCC CEO Prof. Dr. Ottmar Edenhofer. “In this way, emissions trading has become a betting shop for political decisions.” In such a context, even rumors of changes, whether real or alleged, can trigger price hikes. “A good countermeasure would be a minimum price for the permits, including the prompt implementation thereof after the ratification of the global climate agreement,” says Edenhofer. Greater price certainty will allow investors to better plan and to switch more readily to carbon-friendly technologies. “In that way, emissions trading could finally also contribute to climate protection.”

Link to the cited study:

Koch, N.; Grosjean, G.; Fuss, S.; Edenhofer, O. (2016:) Politics matters: Regulatory events as catalysts for price formation under cap-and-trade, in: Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Volume 78, July 2016, Pages 121–139, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0095069616300031

Source

Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) gGmbH 2016