Wind and solar replacing coal power’s share in G20 countries

Pathways aligned with 1.5C require rapid reductions in coal power this decade.

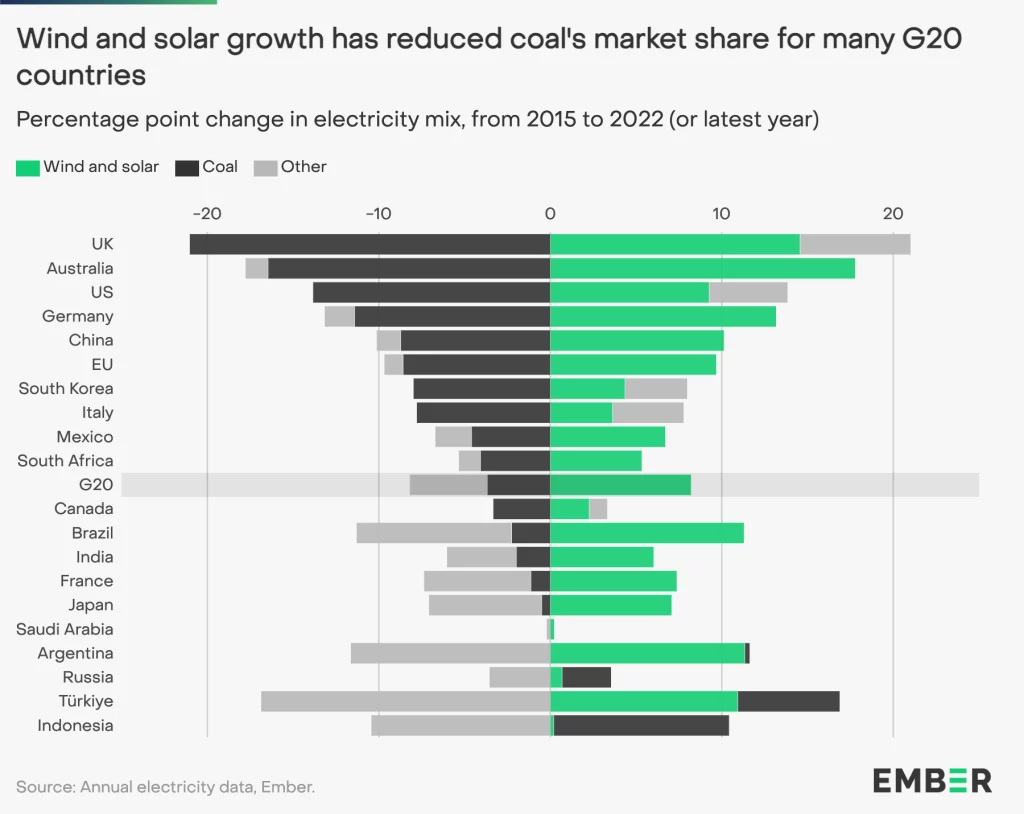

Wind and solar have reduced the share of coal power in G20 countries since the Paris Agreement, according to an analysis of data from the fourth annual Global Electricity Review published by energy think tank Ember. However, the transformation is not yet happening fast enough for a pathway aligned with 1.5C, although there are positive signs.

The data reveals that in G20 countries, wind and solar reached a combined share of 13% of electricity in 2022, up from 5% in 2015. In this period, the share of wind power doubled and the share of solar power quadrupled. As a result, coal power fell from 43% of G20 electricity in 2015 to 39% in 2022. Shares of other sources of electricity remained broadly stable, with fluctuations of just 1-2 percentage points. However, 13 of the G20 still have over half of their electricity from fossil fuels as of 2022. Saudi Arabia stands out with almost 100% of its electricity from oil and gas. South Africa (86%), Indonesia (82%) and India (77%) are the next most reliant on fossil – all predominantly coal – generation.

https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/13710775/embed?auto=1

According to the IPCC, wind and solar can deliver over a third of the emissions cuts required in 2030 to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees. Encouragingly, half of these emissions reductions from wind and solar would actually save money compared to the reference scenario.

“Replacing coal power with wind and solar is the closest thing we have to a silver bullet for the climate,” said Malgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, senior analyst at Ember. “Not only do solar and wind cut emissions fast, they also bring down electricity costs and reduce health-harming pollution.”

Across the G20, progress towards wind and solar power is mixed. The leaders are Germany (32%), the UK (29%) and Australia (25%). Turkey, Brazil, the US and China have consistently held above the global average. At the bottom are Russia, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia with nearly zero wind and solar power in their mix.

Thirteen of the G20 still have over half of their electricity from fossil fuels as of 2022. Saudi Arabia stands out with almost 100% of its electricity from oil and gas. South Africa (86%), Indonesia (82%) and India (77%) are the next most reliant on fossil – all predominantly coal – generation.

OECD countries in G20 accelerate to 2030 coal phase-out

Among advanced (OECD) economies in the G20, which should target coal phase-out by 2030, there has been a reduction in coal generation by 42% in absolute terms from 2,624 TWh in 2015 to 1,855 TWh in 2022.

The fastest decline in coal power in the G20 has been achieved by the United Kingdom, which reduced its coal generation by 93% since the Paris Agreement was signed, falling from 23% of electricity in 2015 to just 2% in 2022. Italy halved its coal power in the same period, while the United States and Germany reduced their coal power by around a third. Even coal-dependent Australia has reduced its share of coal power from 64% in 2015 to 47% in 2022. Among advanced economies in the G20, Japan stands out as it has yet to reduce its share of coal power, which remains around a third of its electricity.

The growth in wind and solar generation has been a key factor in the success of these OECD countries in reducing coal power. The UK and Germany stand out with the highest shares of wind power at 25% and 22% in 2022, while Australia and Japan top the G20 for solar power share at 13% and 10% in 2022.

Despite encouraging progress in mature economies, the decline in coal power needs to accelerate even faster this decade. According to the IPCC, global unabated coal power needs to fall by 87% this decade, from 10,059 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2021 to 1,153 TWh in 2030. The majority of this fall needs to happen in G20 countries, which were responsible for 93% of the world’s total coal generation in 2022.

Although the G20’s share of coal power has reduced since the Paris Agreement, the absolute generation of coal power has increased as countries turn to coal to meet rising demand. In 2015, G20 countries generated 8,565 TWh of coal-fired electricity, increasing by 11% to 9,475 TWh in 2022. This increase is being driven by five key countries.

Five G20 countries yet to peak coal emissions

Just five G20 nations have seen coal increase in absolute terms since 2015: China (+34%, +1374 TWh), India (+35%, +357 TWh), Indonesia (+52%, +65 TWh), Russia (+31%, +47 TWh) and Türkiye (+50%, +37 TWh). Among those, China and India have been able to reduce the percentage share of coal in that period, as they focus on scaling up wind and solar to meet rising demand. China generated 70% of its electricity from coal in 2015, reducing it to 61% in 2022. India achieved a smaller decline, from 76% of electricity from coal in 2015 to 74% in 2022. However, Indonesia, Russia and Türkiye have all seen their share of coal power increase.

There are signs that these countries are nearing ‘peak’ coal emissions, as clean power is close to growing quickly enough to meet all growth in demand. In China, wind and solar met 69% of the growth in electricity demand in 2022, while all clean sources met 77%. Over half of the electricity demand rise in Asia (52%) was met with clean electricity in the seven years from 2015 to 2022, double the 26% achieved in the seven years before that. Peaking emissions is the first step, how fast the phasedown of fossil fuels then happens will depend on actions taken by governments to accelerate the deployment of wind and solar.

“Power sector decarbonisation is the single biggest action needed to cut emissions,” said Malgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, senior analyst at Ember. “G20 countries are mostly already moving towards a cleaner electricity system but this now needs to be accelerated. The cheapest and fastest way to achieve that will be through the rapid roll out of proven technologies–wind and solar–not through gambling on unproven technologies like fossil fuels with carbon capture. G7 members have agreed to predominantly decarbonise their power sectors by 2035, and making explicit their commitments on the speed of deployment of solar and offshore wind. There have not yet been similar discussions in the G20, and given that it is the most critical barrier to keeping to 1.5 degrees, it needs to be top of the agenda.”