How humanity can accomplish a just climate transition

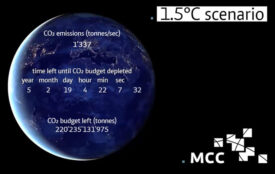

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, no more than 320 gigatonnes of CO2 can be permanently released into the atmosphere if global heating is to be limited to 1.5 degrees. But how do recent net zero pledges affect global equity?

A new study led by the Berlin-based climate research institute MCC (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change) sheds light on how the decarbonisation of the global economy can proceed based on principles of fair burden sharing. The study has now been published in the renowned journal Climatic Change.

Equity is an essential feature of global climate diplomacy. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change adopted in 1992 speaks of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, and the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 deliberately provides latitude for differing national efforts, with a view to affordability, state of development, and historical emissions. “How to account for national circumstances and still meet the global temperature targets agreed in Paris will be a key issue at the upcoming World Climate Summit in Glasgow,” says Dominic Lenzi, a researcher in the MCC working group Scientific Assessments, Ethics and Public Policy and lead author of the study. “With our paper, we want to highlight the importance of the equity dimension when turning net zero pledges into policy”.

To explore the options for achieving an equitable net zero future, the team of authors conducted a thought experiment based on three stylised future pathways, each of which is compatible with the 1.5-degree target. These pathways involve: (1) all countries achieving climate neutrality by 2050, (2) industrialised countries achieving climate neutrality by 2030, while the non-industrialised countries having time until 2070, and (3) the world taking out an “overdraft” on the atmosphere with climate neutrality being achieved by industrialised countries in 2050 and non-industrialised countries in 2080. Under these three future pathways, the study systematically explores the potential equity effects of carbon pricing with border carbon tariffs, financial transfers, and atmospheric carbon removal technologies:

- The overdraft credit only works with massive expansion of atmospheric carbon removal. As things stand today, this would most likely be achieved through carbon capture and storage associated with combustion of fast growing biomass from climate plantations. The most cost-effective locations for this are in the Global South – which would face risks of unfair and unsustainable demands on land and water, along with problems for food security and biodiversity.

- A turbo-charged conversion of the industrialised countries to a fossil-free economy by 2030 would be conceivable, at best, in combination with the intensive use of border carbon adjustment to protect domestic industry. This would mean export barriers for suppliers from the Global South, which would slow down economic and social development.

- For the “climate neutrality 2050 in lockstep” scenario not to be completely unrealistic, financial aid from the industrialised countries to the rest of the world would have to be scaled up massively. While this would accord with common views of fair burden sharing, it could create dependencies, currency turbulence and misaligned incentives among recipients, and might also be difficult to communicate in donor countries.

“None of these ways forward to global net zero emissions appear unequivocally good or bad, and it matters greatly how policies are implemented,” emphasises MCC researcher Lenzi. “Quantitative model studies based on our three stylised pathways could help to more accurately gauge the global areas of tension between climate mitigation and equity. Policymakers need to clarify how their visions for global decarbonisation are both effective and fair.”

- Reference of the cited article: Lenzi, D., Jakob, M., Honegger, M., Droege, S., Heyward, J., Kruger, T., 2021, Equity implications of net zero visions, Climatic Change