Self-heating, fast-charging battery makes electric vehicles climate-immune

Californians do not purchase electric vehicles because they are cool, they buy EVs because they live in a warm climate. Conventional lithium-ion batteries cannot be rapidly charged at temperatures below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, but now a team of Penn State engineers has created a battery that can self-heat, allowing rapid charging regardless of the outside chill.

“Electric vehicles are popular on the west coast because the weather is conducive,” said Xiao-Guang Yang, assistant research professor in mechanical engineering, Penn State. “Once you move them to the east coast or Canada, then there is a tremendous issue. We demonstrated that the batteries can be rapidly charged independently of outside temperature.”

When owners can recharge car batteries in 15 minutes at a charging station, electric vehicle refueling becomes nearly equivalent to gasoline refueling in the time it takes. Assuming that charging stations are liberally placed, drivers can lose their “range anxiety” and drive long distances without worries.

Previously, the researchers developed a battery that could self-heat to avoid below-freezing power drain. Now, the same principle is being applied to batteries to allow 15-minute rapid charging at all temperatures, even as low as minus 45 degrees F.

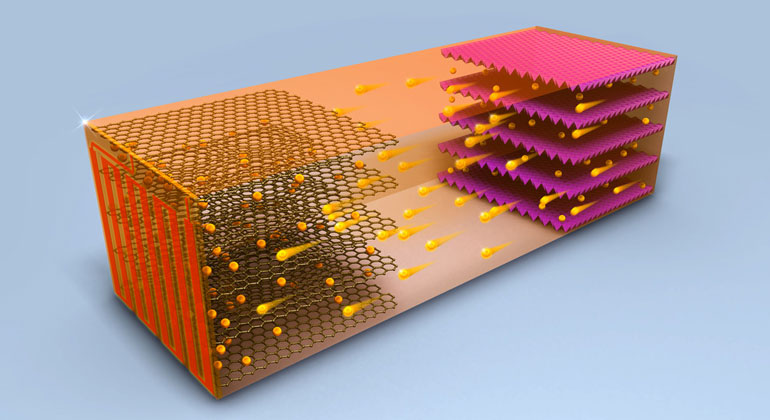

The self-heating battery uses a thin nickel foil with one end attached to the negative terminal and the other extending outside the cell to create a third terminal. A temperature sensor attached to a switch causes electrons to flow through the nickel foil to complete the circuit when the temperature is below room temperature. This rapidly heats up the nickel foil through resistance heating and warms the inside of the battery. Once the battery’s internal temperature is above room temperature, the switch turns opens and the electric current flows into the battery to rapidly charge it.

“One unique feature of our cell is that it will do the heating and then switch to charging automatically,” said Chao-Yang Wang, Chao-Yang Wang, William E. Diefenderfer Chair of mechanical engineering, professor of chemical engineering and professor of materials science and engineering, and director of the Electrochemical Engine Center. “Also, the stations already out there do not have to be changed. Control off heating and charging is within the battery, not the chargers.”

The researchers report the results of their prototype testing in this week’s edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They found that their self-heating battery could withstand 4,500 cycles of 15-minute charging at 32 degrees F with only a 20-percent capacity loss. This provides approximately 280,000 miles of driving and a lifetime of 12.5 years, longer than most warranties.

A conventional battery tested under the same conditions lost 20-percent capacity in 50 charging cycles.

Lithium-ion batteries degrade when rapidly charged under 50 degrees F because, rather than the lithium ions smoothly integrating with the carbon anodes, the lithium deposits in spikes on the anode surface. This lithium plating reduces cell capacity, but also can cause electrical spikes and unsafe battery conditions. Currently, long, slow charging is the only way to avoid lithium plating under 50 degrees F.

Batteries heated above the lithium plating threshold, whether by ambient temperature or by internal heating, will not exhibit lithium plating and will not lose capacity.

“This ubiquitous fast-charging method will also allow manufacturers to use smaller batteries that are lighter and also safer in a vehicle,” said Wang.

Also working on this project were Guangsheng Zhang former postdoctoral scholar in mechanical engineering, and Shanhai Ge, assistant research professor of mechanical engineering, Penn State.