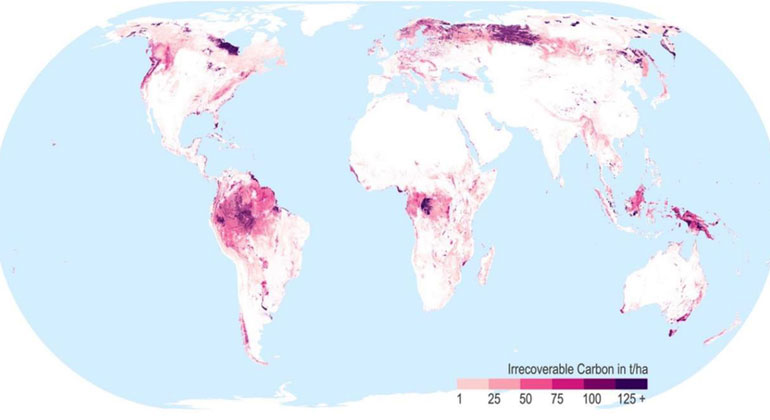

World map of the most important protected areas to avert a climate catastrophe

New research out today from Conservation International maps the places on Earth that humanity must protect to avoid a climate catastrophe. These ecosystems contain what researchers call “irrecoverable carbon,” dense stores of carbon that, if released due to human activity, could not be recovered in time for the world to prevent the most dangerous impacts of climate change.

These stores, which researchers call “irrecoverable carbon”, are primarily mangroves, tropical forests and peatlands, as well as old-growth forests in temperate latitudes. The special protection of these crucial areas has another advantage: they are also havens of biodiversity. Thus, the targeted protection of these irretrievable carbon reservoirs can simultaneously make a significant contribution to species conservation.

“The consequences of releasing this stored carbon would stretch on for generations, undermining our last chance to stabilize Earth’s climate at tolerable levels for nature and humanity,” said Johan Rockström, Conservation International chief scientist and co-director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, a leader in climate and sustainability research. “We must act now to safeguard the planet’s ability to serve as a carbon sink, which includes prioritizing these unique ecosystems.”

The new worldwide map, published today in the journal Nature Sustainability, shows that half of Earth’s irrecoverable carbon is highly concentrated on just 3.3% of land – primarily old-growth forests, peatlands and mangroves. These vast reserves of carbon are equivalent to 15 times the global fossil fuel emissions released last year.

Researchers say that knowing which ecosystems contain the greatest irrecoverable carbon stores can help governments focus global efforts to protect 30% of land by 2030. Targeted conservation would yield big gains – increasing the land under protection key areas by just 5.4% would keep 75% percent of Earth’s irrecoverable carbon from being released into the atmosphere, researchers found.

An accompanying report, also released today, reveals that many of these irrecoverable carbon areas overlap with places containing high concentrations of biodiversity – meaning that protecting lands essential for climate stability would also conserve habitats for thousands of mammal, bird, amphibian and reptile species. The paper calls for the creation of “irrecoverable carbon reserves,” new, area-based conservation measures designed to ensure irrecoverable carbon remains in these critical ecosystems.

According to the Nature Sustainability study, the largest and highest-density irrecoverable carbon ecosystems include

- The tropical forests and peatlands of the Amazon biome (31.5 Gigatonnes irrecoverable carbon);

- The Congo Basin (8.2 Gigatonnes);

- Islands of Southeast Asia (13.1 Gigatonnes);

- The temperate forests of northwestern North America (5.0 Gigatonnes);

- Mangroves, seagrasses and tidal wetlands globally (4.8 Gigatonnes).

The study also details how vulnerable irrecoverable carbon areas are to human activity and climate change – and how much irrecoverable carbon is stored within Indigenous and protected lands.

These key findings include

- 52% of the world’s irrecoverable carbon currently lacks any formal protection or management;

- More than a third of irrecoverable carbon (46.7 billion gigatonnes) is stored within the government-recognized lands of Indigenous peoples and local communities;

- Across ecosystems, the highest concentrations of irrecoverable carbon are found in mangroves (218 tonnes per hectare, on average), tropical peatlands (193 t/ha) and boreal wetlands (173 t/ha).

- Read the entire study: „Mapping the irrecoverable carbon in Earth’s ecosystems“

- Link to interactive CI world map