Arctic sea ice loss could dry out California

Arctic sea ice loss of the magnitude expected in the next few decades could impact California’s rainfall and exacerbate future droughts, according to new research led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) scientists

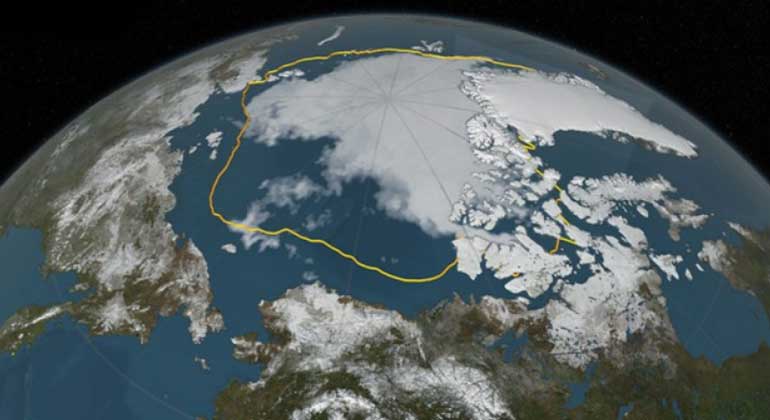

The dramatic loss of Arctic sea ice cover observed over the satellite era is expected to continue throughout the 21st century. Over the next few decades, the Arctic Ocean is projected to become ice-free during the summer. A new study by Ivana Cvijanovic and colleagues from LLNL and University of California, Berkeley shows that substantial loss of Arctic sea ice could have significant far-field effects, and is likely to impact the amount of precipitation California receives. The research appears in the Dec. 5 edition of Nature Communications (link is external).

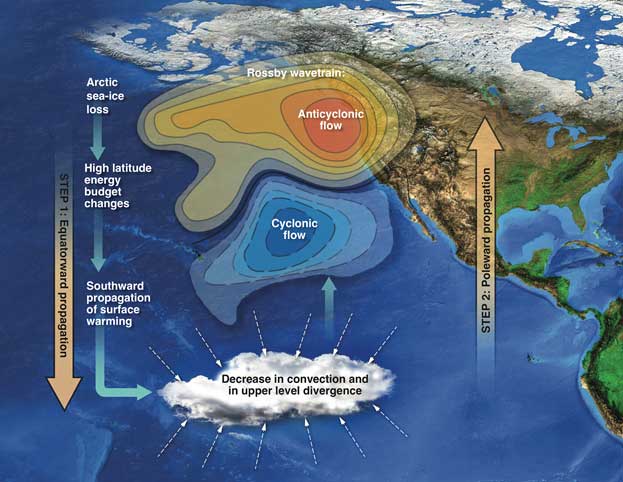

The study identifies a new link between Arctic sea ice loss and the development of an atmospheric ridging system in the North Pacific. This atmospheric feature also played a central role in the 2012-2016 California drought and is known for steering precipitation-rich storms northward, into Alaska and Canada, and away from California. The team found that sea ice changes can lead to convection changes over the tropical Pacific. These convection changes can in turn drive the formation of an atmospheric ridge in the North Pacific, resulting in significant drying over California.

“On average, when considering the 20-year mean, we find a 10-15 percent decrease in California’s rainfall. However, some individual years could become much drier, and others wetter,” Cvijanovic said.

The study does not attribute the 2012-2016 drought to Arctic sea ice loss. However, the simulations indicate that the sea-ice driven precipitation changes resemble the global rainfall patterns observed during that drought, leaving the possibility that Arctic sea-ice loss could have played a role in the recent drought.

“The recent California drought appears to be a good illustration of what the sea-ice driven precipitation decline could look like,” she explained.

California’s winter precipitation has decreased over the last two decades, with the 2012-2016 drought being one of the most severe on record. The impacts of reduced rainfall have been intensified by high temperatures that have enhanced evaporation. Several studies suggest that recent Californian droughts have a manmade component arising from increased temperatures, with the likelihood of such warming-enhanced droughts expected to increase in the future.

“Our study identifies one more pathway by which human activities could affect the occurrence of future droughts over California — through human-induced Arctic sea ice decline,” Cvijanovic said. “While more research should be done, we should be aware that an increasing number of studies, including this one, suggest that the loss of Arctic sea ice cover is not only a problem for remote Arctic communities, but could affect millions of people worldwide. Arctic sea ice loss could affect us, right here in California.”

Other co-authors on the study include Benjamin Santer, Celine Bonfils, Donald Lucas and Susan Zimmerman from LLNL and John Chiang from the University of California, Berkeley.

The research is funded by Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. Cvijanovic and Bonfils were funded by the DOE Early Career Research Program Award and Lucas is funded by the DOE Office of Science through the SciDAC project on Multiscale Methods for Accurate, Efficient and Scale-Aware Models of the Earth System.